This article on the science of how your hormones work to regulate your sleep and wake was written by Russel M. Walters, PhD, Chief Science Officer at Somn.

The sleep/wake hormones: melatonin, cortisol & testosterone

We all live according to our circadian rhythm, a near 24-hour internal clock that controls how our body’s functions change throughout the day. Your cognition, metabolism, sleep-wake cycle, and many other functions all follow a circadian rhythm. And because each of us is unique, there are differences in the hormone levels that our bodies produce during that 24-hour period.

At Somn we understand that individual differences in key sleep related hormones require a personalized approach to improving your sleep. That’s why we have created the Somn Personal Sleep & Stress Test, an easy at-home program designed to help you understand, and then take action for better sleep and stress management, all according to your specific needs.

Melatonin is a key hormone produced by our bodies to help bring us into sleep. If you’ve tried melatonin supplements before, and they didn’t work for you… you’re not alone. With literally thousands of choices and random recommended dosing, melatonin purchased at your local pharmacy or online retailer is likely not going to be ideal for you. Your unique sleep needs require a more personalized melatonin solution.

Cortisol

Cortisol is the primary stress hormone produced by our bodies – think of it as nature’s built in alarm system. It’s best known for helping fuel your body’s “fight-or-flight” instinct in a crisis. Cortisol levels start to rise approximately 2-3 hours after sleep onset and continue to rise into the early morning and early waking hours. The peak in cortisol is about 9 a.m.; as the day continues, levels decline gradually. And there are individual variations in peak cortisol levels as well as in the timing for our bodies to reach peak and gradually reduce cortisol. Strategies and products to effectively reduce cortisol require a personalized approach.

Testosterone is well known as the primary male sex hormone, however it also has a role in sleep and performance. And the variation in testosterone levels through the day has been well documented including variation between individuals based on age and other factors such as stress. See below for more background on these three hormones and how they impact your sleep.

Like nearly all hormones in the human body, cortisol has a daily, 24-hour circadian rhythm. For most biotypes, cortisol levels are at their highest in the morning, usually around 9 a.m. Cortisol begins to rise gradually in the second half of a night’s sleep. The hormone begins a more rapid rise around the time you’re waking up before peaking at about 9am. From that point on, cortisol makes a gradual decline throughout the day, reaching its lowest levels around midnight. The activity of the HPA axis (short for hypothalmic-pituitary-adrenal axis), which produces cortisol, reduces to its lowest levels in the evenings, right around your bedtime. In this way, cortisol plays a critical role in sleep-wake cycles: stimulating wakefulness in the morning, continuing to support alertness throughout the day, while gradually dropping to allow the body’s own internal sleep drive and other hormones—including adenosine and melatonin—to rise and help bring about sleep.

That’s cortisol and its rhythm in balance, or homeostasis. Too often, the cortisol rhythm is thrown out of sync, leading to problems with sleep and health. Cortisol levels can be too low, but much more often, it’s elevated cortisol that’s the problem.

Chronic stress is a major contributor to elevated cortisol, an excessively active HPA axis, and an ongoing state of arousal that’s exhausting, anxiety-producing, and sleep-depriving. Elevated cortisol also contributes to a compromised immune system, chronic inflammation, weight gain, and, eventually, to chronic disease.

Poor sleep itself also can increase cortisol production and dysfunction of activity along the HPA axis. Research shows that cortisol can be elevated by:

- Poor-quality sleep

- Lack of sufficient sleep

- Inconsistent sleep schedules (including rotating schedules adhered to by shift workers)

Research shows a complex two-way street between the HPA axis (which produces cortisol and regulates its levels) and sleep. Poor, insufficient, irregular sleep increases the activity of that system, leading to more stress, greater arousal, and, over time, to the health complications mentioned above. And a more active HPA axis can interfere with the ability to maintain consistent sleep routines and to get enough sound, high-quality sleep. It can be a vicious cycle.

A personalized medicine approach may help in giving you strategies to manage your cortisol levels for improved sleep and daytime performance.

Testosterone

When it comes to sleep, testosterone may be the somewhat forgotten hormone. We know a great deal about the importance of testosterone as the male sex hormone, its role in the body and the effects of testosterone deficits, particularly for men. But there’s been relatively little attention paid to the effects of testosterone on sleep, for both men and women.

Changes in testosterone levels occur naturally during sleep, both in men and women. Testosterone levels rise during sleep and decrease during waking hours. Research has shown that the highest levels of testosterone happen during REM sleep, the deep, restorative sleep that occurs mostly late in the nightly sleep cycle. Sleep disorders, including interrupted sleep and lack of sleep reduces the amount of REM sleep, will frequently lead to low testosterone levels. And this is important for men and women.

There’s strong evidence of a relationship between testosterone and sleep disordered breathing, including obstructive sleep apnea. Men with obstructive sleep apnea are also more likely to suffer from complications to their sexual function, including low libido, erectile dysfunction, and impotence. Men who are struggling with issues related to sexual function should have their sleep evaluated by their physician.

What are the implications for women of low testosterone levels from lack of sleep? Women are particularly vulnerable to sleep problems related to hormone changes and deficiencies, throughout their lives. We talk most frequently about estrogen and progesterone, the primary hormones involved in menstruation. But testosterone should be added to the list of hormonal factors to consider when thinking about hormone-related sleep problems in women.

The more we know about how testosterone affects sleep and sexual health in men and women, the better clinicians will be able to help restore healthy functioning to two critical aspects of our lives.

Melatonin

Melatonin serves a key role in managing your body’s biological clock as well as managing your sleep and wake cycles. Under normal conditions, the body produces melatonin in the evening and overnight. Also melatonin is commonly taken as a supplement. Despite the lack of evidence, melatonin is widely used for a range of sleep problems, well beyond just difficulty in falling asleep. People commonly take exogenous melatonin for difficulty staying asleep and also for difficulties waking too early in the morning.

While many people have tried melatonin as a sleep aid, many people also stop after trying it,

suggesting that melatonin is not solving sleep sufferers’ problems under the conditions that it is being used. A personalized medicine approach may be a path to improving the effectiveness of melatonin supplements for sleep sufferers.

Zeitgebers

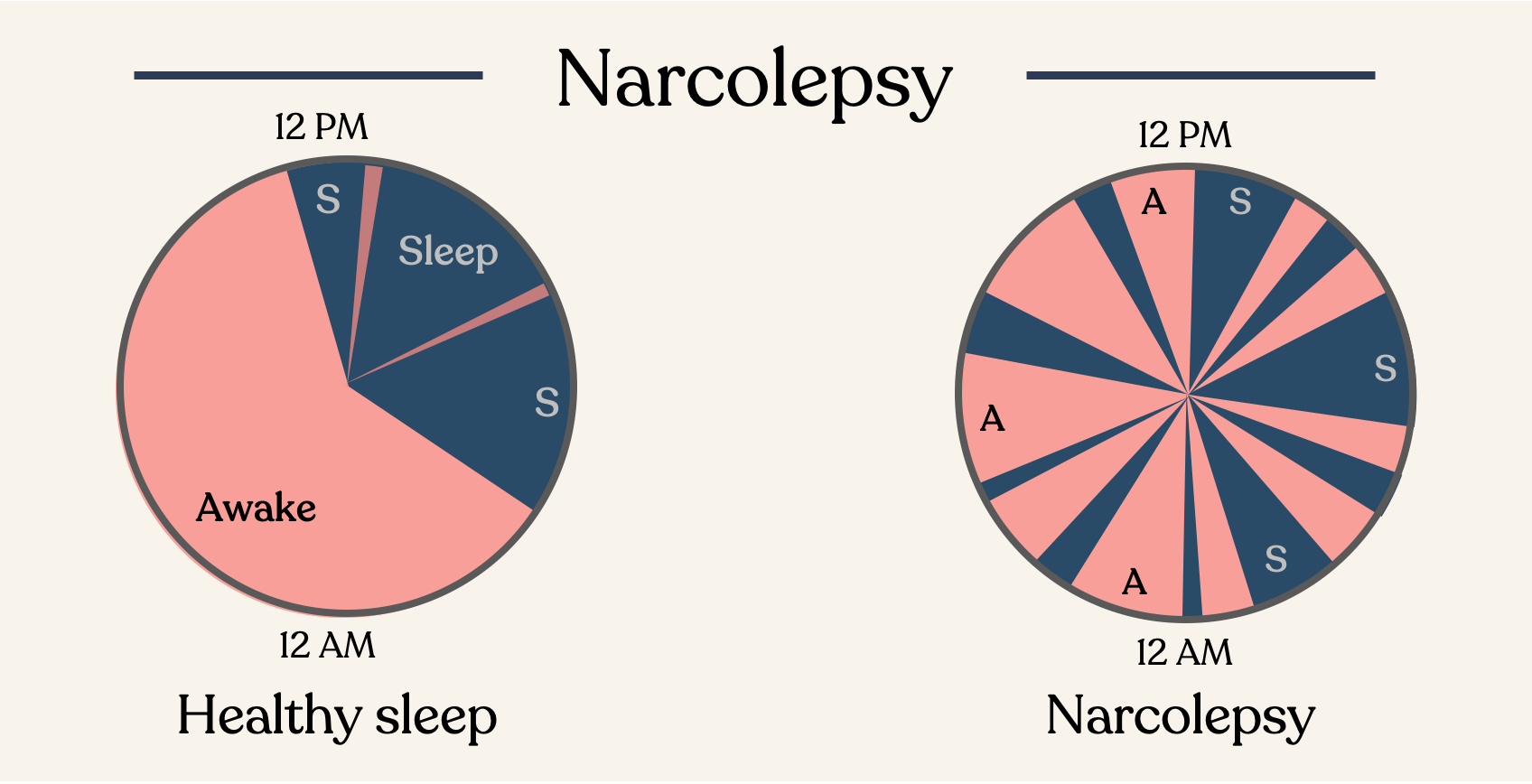

We need to first understand what is sleep and what determines how much we sleep. Sleep is not a passive event, but rather an active process involving physiological changes that occur throughout the brain and body (Guidozzi, 2015). Sleep is governed by two processes (Borbély, 1982): one oversees the time of day to sleep during a 24-hour period (Daan et al., 1984) and the other gauges the need for sleep (Achermann & Borbély, 2011).

Your need for sleep is determined by circadian rhythms and the interaction of these processes defines the timing and duration of your sleep. Throughout the day or with extended wakefulness, our sleep pressure increases and thus, the need for sleep increases (Dijk & Franken, 2005). Yet, many factors such as genetics, feeding, exercise, stress, menstrual cycle, hormones, and medications also influence our sleep need.

Circadian biology

Different factors affect specific parts of sleep. Our internal clock, which is present in cells and neurons in the body, is influenced by light-dark cycles as well as eating (Santhi et al. 2016). This clock plays an important role in the sleep/wake cycle and enables the transition of different sleep cycles (Guidozzi, 2015). Circadian rhythms influence not only our sleep but also alertness, mood, hormone release, all of which are controlled by our internal clock (Achermann & Borbély, 2011).

Due to changes in reproductive development and changes in melatonin, a hormone that alters sleep, adolescents experience many changes in their sleep-wake cycle. During this age span, there is reduced deep sleep (N3) and REM sleep as well as an increase in delayed sleep phase. (Jenni and Carskadon, 2004; Jenni et al., 2005; Kurth et al., 2010; Lui et al., 2017). In other words, adolescents are going to bed later and not getting enough of the deep sleep they need to feel rested and refreshed.

Learn about the Somn Sleep & Stress Test