We explored how bed comfort and sleep are related based on self-reported sleep patterns and perception of sleep. Do more comfortable beds lead to better sleep? Can you buy better sleep?

Methods: 3,007 adults completed an expanded version of the Somn Sleep Assessment that included questions about their bed comfort and their sleep.

Data Question 1: Does bed comfort affect sleep?

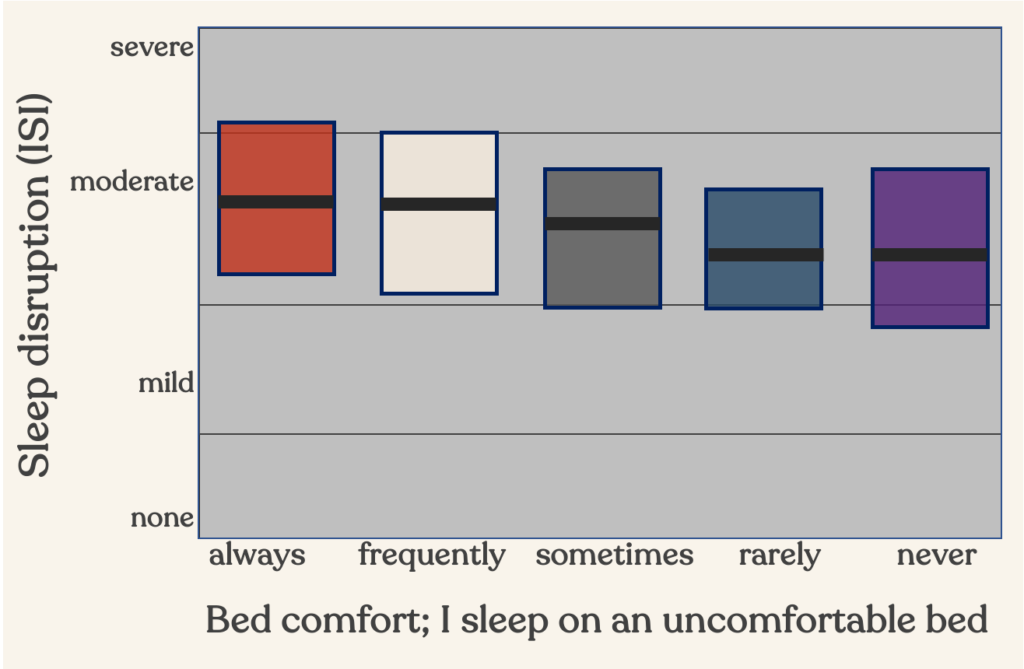

The first clear finding is that a lot of people are sleeping on “bad” beds: over 20% of subjects reported sleeping on an uncomfortable bed either “always” or “frequently.” People who are sleeping on uncomfortable beds also report worse sleep, with significantly higher insomnia scores (15.1 vs 16.9), p<0.001. Sleep onset latency, or how long it takes to fall asleep, was an average of 20 minutes longer for those who “always” sleep on an uncomfortable bed compared to those that said they “never” do.

Correspondingly, all this bad sleep on an uncomfortable mattress results in being tired during the day. So it’s not surprising that bed discomfort was associated with daytime sleepiness (higher Epworth Daytime Sleepiness scores, 8.3 vs 9.5, p<0.001). Furthermore, reported bed comfort was highly correlated with alertness at work (p<0.001). Maybe you can talk your employer into buying you a new bed!

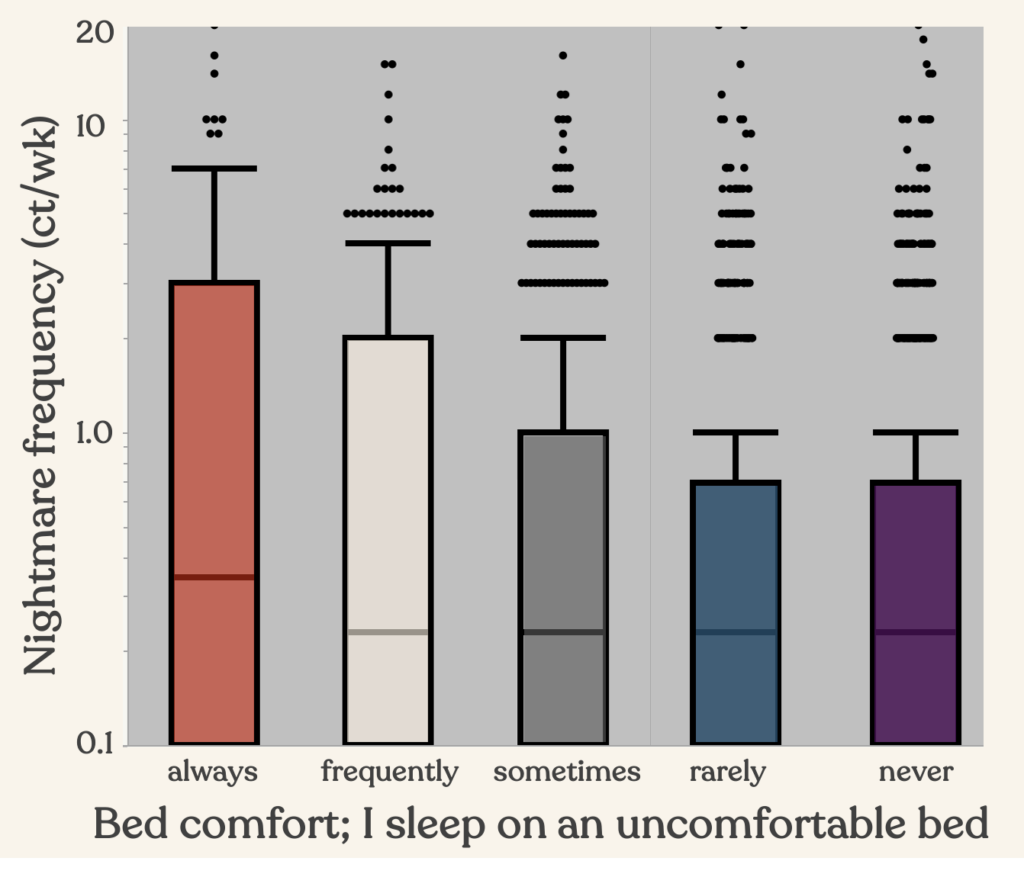

Data Question 1.1: So is an uncomfortable bed a nightmare?

Well maybe, but we didn’t exactly explore that. One interesting thing we did learn was that nightmare frequency was significantly higher for those who slept on an uncomfortable bed (1.62 nightmares/wk vs 0.91/wk, p<0.001). Speculating, perhaps, that because sleep is less sound on an uncomfortable mattress, more dreams and nightmares are remembered.

Conclusion 1: Yes – Uncomfortable beds are correlated with bad sleep

Based on the two questions above, bed discomfort is clearly associated with worse sleep, though we can’t explicitly know the causality. This is an important question: should people who are unhappy with their sleep begin by changing their behaviors or changing their bed… or both? In many ways, changing a bed is much easier than sustained behavior change, or habitual behaviors.

Data Question 2: Can money buy you happiness in your sleep?

Previous sleep-related studies have shown that wealthier sleepers often have more complaints. This is markedly so in the case of baby sleep: wealthier parents tend to report more problems with their children’s sleep, even though their children actually tend to sleep a little better than children from lower socioeconomic groups. Like The Princess and the Pea, when you have more wealth does that just lead to more complaints?

In the Somn Sleep Assessment research, perception of bed comfort was positively correlated with both age and income. 28% of subjects with household income below $30,000 reported an uncomfortable bed compared with only 8.0% of subjects with household incomes over $130,000. To be clear, from this data we could only correlate sleep with household income, and not how much a bed cost. But there is likely a very strong correlation between household income and bed cost.

Conclusion 2: Yes – You can buy better sleep with a comfortable mattress

With bed comfort, money does seems to buy bed happiness. It appears that you can buy happy sleep, with a quality new mattress. This is supported by separate research that showed that replacing an old mattress reduced back pain and improved sleep.

Is it time for a new mattress?

- Here are 14 Tell-tale Signs You Need A New Mattress.

- Explore the natural form mattress; better sleep naturally

- Read about the personalized Helix mattress; meet your match

- Learn about the Somn Sleep Assessment

Here is the full abstract from this data that was presented at SLEEP 2019.

Explore Your Sleep

Title: Bed comfort and sleep: change your bed or change your behavior?

Authors: Russel M. Walters, Jordana Composto

Introduction: We explored how bed comfort was related to self-report sleep patterns and perception of sleep.

Methods: 3,007 adults (2,793 females) between the ages of 18 to 86, recruited through social media, completed a comprehensive online sleep assessment modified for mobile experience, including the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), Sleep Hygiene Index, and questions about attempted sleep solutions.

Results: 20.4% of subjects reported sleeping on an uncomfortable bed either “always” or “frequently.” The perception of bed comfort was positively correlated with both age and income. 28% of subjects with household income less than $30,000 reported an uncomfortable bed compared with only 8.0% of subjects with incomes over $130,000. Participants who reported sleeping on an uncomfortable bed had significantly higher ISI scores (15.1 vs 16.9), p<0.001.

Self-reported sleep onset latency (SOL) was associated with bed discomfort, with an average 20 minutes longer SOL for those that “always” sleep on an uncomfortable bed compared to “never.” Bed comfort was not associated with number or duration of night wakings. Nightmare frequency was also significantly higher for those that slept on an uncomfortable bed (1.62 nightmares/wk vs 0.91/wk, p<0.001). Bed discomfort was associated with daytime sleepiness with higher ESS scores (8.3 vs 9.5), p<0.001. Furthermore, reported bed comfort was significantly correlated with alertness at work (p<0.001).

Conclusions: While bed discomfort is clearly associated with increased likelihood of insomnia, nightmares, and daytime sleepiness, we cannot know explicitly the direction of the causality. This is an important question that needs more exploration. Should individuals who report poor sleep and an uncomfortable bed begin by changing behaviors or changing their bed… or both?